Remembering Trans Lives, Resisting Trans-misogynoir, and Reimagining Trans Futures

An article by Jamie Anderson, Pedrom Nasiri, and the GSA Gender and Sexuality Alliance Subcommittee

November 20th marks Trans Day of Remembrance (TDoR) which has become “the largest multi-venue transgender event in the world”[1]. In 1999, TDoR was started by Gwendolyn Ann Smith in response to the murder of Rita Hester, a Black trans woman, the year prior[2]. When news of Rita’s death emerged, community members not only grieved her loss, but had to fight to have her recognized respectfully within media accounts of her murder. Looking to gather data to make sense of violence experienced by transgender people, Smith realized that such information was hard to find. In the decades since Rita’s death, efforts to gather information about transphobic violence around the world continue to grow and this knowledge mobilization has become a critical part of Trans Day of Remembrance, while we remember those community members who have been murdered. Unfortunately, this data is almost always incomplete for numerous reasons: because health care and justice systems refer to people using their legal names or sex markers; because many trans folks experience homelessness or are sex workers and go “missing” without being looked for; because violence may be attributed to other causes or be dismissed as unrelated to identity; and because in death, people’s identities may be misrepresented by their families or the state.

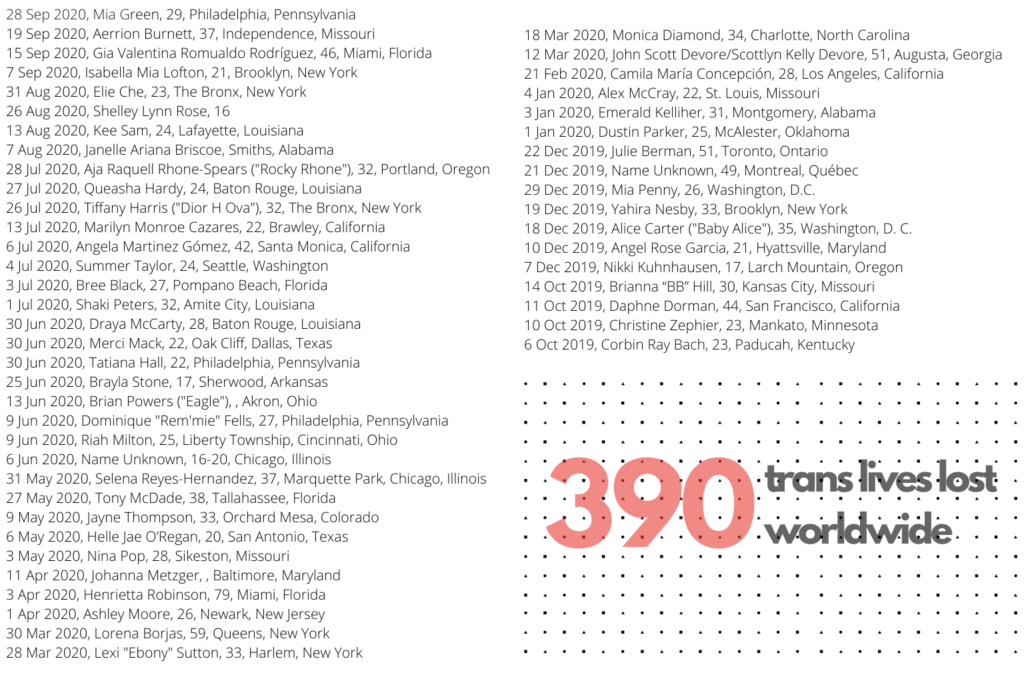

Although TDoR brings us together to mourn those that have died as a result of transphobic violence, we need to recognize that such violence cannot be disentangled from the hierarchies of race, gender, and class[3]. There is no one trans experience, but trans identities remain incredibly vast and varied. Attempting to fit all of us all under one umbrella only pushes some of us further to the margins, towards erasure. As we remember the trans lives lost in the last year, we hold space for their complexities as humans: their beauty, resilience, resistance, power, and their full spectrums of good, bad, and otherwise. We honour each and every one of their lives and we grieve each and every loss. It is with deep sadness that we cite and recite the following names of our dear trans kin lost in the last year.

The Politics of Memorializing

November marks a month of collective remembrance in Canada, with Remembrance Day commemorated on November 11th and Trans Day of Remembrance following shortly after on November 20th. We are already immersed in politics forgetfulness in that we have to mark our calendars year after year to take time for the recognition of loss, or, in the case of TDoR, the recognition of existence by way of loss[4]. As we reflect on our transgender kin and consider ways in which we can honour their lives, dignity, and futures, we also need to reconsider how we take up such memorialization. Where does our remembrance sit within a crisis that sees exceedingly more Black, Brown, and Indigenous trans folks (primarily women and femmes) dying year after year? And how might we make the lives of racialized trans folks’ matter in life, and not only in death?

Approaches to remembrance in Canada often situate human loss within grander narratives of national progress. On Remembrance Day, ceremonies recognize the deaths of soldiers as tragic, yet necessary to achieve the goals of the Canadian nation-state and create the political and social structures of nationhood that exist today. In the weeks before TDoR each year, symbols of remembrance cue us to take up a somber gratitude; a gratitude which can lead us to normalize the expendability of some human life in the name of progress for others. In doing so, we remove these deaths from the intentional structures, policies, and politics that are responsible for them. We can no longer take up a remembrance that forgets the humanity of people, particularly trans people, for the benefit of others. As we engage in remembrance of our trans kin, we need to resist reducing our concerns into the “singular” issue of transphobia, as though transphobia is not also articulated through racism, sexism, and classism. As we take up a position of mourning for our trans kin, it is necessary to examine how we contribute to conditions that continue to leave Black, Brown, and Indigenous trans women the most vulnerable to structural and interpersonal violence.

Structures and Conditions of Violence

Between October 1st, 2019 and September 30th, 2020, there were 390 deaths attributed to transphobic violence around the world[5]. A vast majority of these deaths were trans women of colour who continue to comprise more than 80% of all anti-trans homicides year after year[6]. This number represents only those deaths that have been reported and only those directly attributed to transphobia, which reminds us that the realities of transphobic violence are starker than our accounting processes can reflect. Although we use this number to make sense of anti-trans violence around the world, we also have to be careful in how this accounting, or “mathematics of unliving,” values trans lives only in their abstract accumulation[7]. In saying their names, not just these numbers, we demand attention to the dehumanizing structures that “continually produce black and trans death”[8].

As we collectively consider the violence against trans people on TDoR, it is necessary to recognize these particularly lethal outcomes as just one symptom of systemic and entrenched transphobia. Anti-trans stigma shows up at home with family rejection, but can be traced further to broader political hostilities, marginalization and erasure. In recent news, author J.K. Rowling has taken up an anti-trans cause, going so far as writing a novel that reinforces harmful transgender stereotypes and characterizes trans women as implicitly threatening. Leveraging her social capital, Rowling has fanned the flames of what is already an epidemic of homicide against trans women. When the dehumanization of trans lives are taken up not only as political fodder, but for personal economic gain, we can see the tangible ways in which transphobia is readily invested in.

Anti-trans discourses have other material impacts that limit the participation of trans and non-binary people in society by way of employment discrimination, workplace harassment, barriers to health care, housing discrimination, unequal policing, and more. Each of these is then exacerbated by existing structures of racism and sexism that see Black transgender people with unemployment rates considerably greater than all transgender folks and exponentially larger than the general population. With media discourses largely focussed on transgender bathroom debates, our attention is directed away from the multiple avenues of dispossession that deprive trans people from rights and resources[9]. Addressing transphobic violence requires us to shift our focus to the economic and social structures that continue to push many Black, Brown, and Indigenous trans women to the margins, limiting access to not only the necessities of life, but the conditions for flourishing in life.

In death, our memorializing practices often sanitize trans lives, situating them in a particular martyrdom, but failing to account for what their everyday lives look like. Censoring the lived experiences of trans folks, particularly those who engage in sex work, suggests that there are “good” trans folks—those who adhere to particular social and cultural norms—and “bad” trans folks, who might negatively impact efforts for trans rights and inclusion. Yet, we forget that for some trans folks, sex work is the most accessible form of employment and offers sources of income in ways that they are otherwise excluded from. In death, we inflict the violence of erasure through censorship, so that particular trans lives can go on living and other trans lives are sacrificed for the sake of progress. If we are to take up a form of grieving that is not only meant to assuage our own guilt, then we have to take seriously our responsibility to Black, Brown, and Indigenous trans women in life, first and foremost. Judith Butler speaks to the ways in which lives are constructed as grievable. To be grievable is to be interpreted “in such a way that you know your life matters; that the loss of your life would matter; that your body is treated as one that should be able to live and thrive”[10]. This notion of grievability, however, does not only relate to those who are dead, but is already operating in life. To grieve trans lives as they are living, is to minimize our(their) precarity and make available provisions for flourishing—economic, social, healthcare, and otherwise.

Transmisogynoir

In our previous article for the GSA’s pride series, called “Challenging Unjust Systems: Pride is a Riot,” we traced the history of pride celebrations to early riots and acts of resistance led by Black, Brown, and Indigenous trans women. Riots at Cooper’s Donut shop, Compton’s Cafeteria, and the Stonewall Inn were a response not only to the criminalization of queer identities, but to the violent policing of sex workers and people of colour who were queer. What we fail to recognize in the romanticization and whitewashing of the Stonewall riots is that Black, Brown, and Indigenous trans women were instrumental in these transformative events because they were resisting a particular kind of homophobia and transphobia that was simultaneously enacted with and through racism and the denigration of sex work.

Ashlee Marie Preston addresses this location of transphobia, misogyny, and anti-black racism—or transmisogynoir—as a social ecology that systematically normalizes violence against Black trans women[11]. Despite leading the way throughout much of the queer liberation movement in Canada and the United States, Black, Brown, and Indigenous trans women have not benefitted from queer inclusion that has taken the form of legalized same-sex marriage, hate crime legislation, or rainbow capitalism, because this “progress” coincides with increased criminalization of sex work, the militarization of police, and homonationalism or the construction of a “normal” and regulated queer body to the Canadian nation-state. So, while some trans bodies (white, gender-conforming, middle class) are shielded by the rainbow flag, even more trans bodies remain most vulnerable to lethal violence that is articulated at the location of transmisogynoir.

Reimagining Trans Futures

As we approach TDoR and grieve those transgender kin who have been lost, we have to remember that “it is not enough to simply honour the dead—we must transform the practices of the living”[12]. Although radical love is an entry point into making trans lives matter, Vivek Shraya reminds us that we can’t love racism, sexism, transphobia away; “love doesn’t keep [our] sisters safe” or protect trans folks from harm[13]. So, we need to shift ourselves “from sympathy to responsibility, from complicity to reflexivity, from witnessing to action”[14]. How can we take into our own lives these memories of others and live as though those lives mattered, and continue to matter?

We want to turn to the important work of Forward Together, a woman of colour-led organization, and their Trans Day of Resilience art project[15]. This online art space is by and for trans people of colour and offers visibility, celebration, nurturance, resistance, and endeavours for a culture shift towards trans liberation[16]. Together, they honour the resilience of trans of colour communities through art, poetry, and with powerful activism. Drawing from their “femifesto,”[17] we want to share some important ways that we can mourn our trans kin, while simultaneously working to challenge the structures that harm us(them).

- Trans rights means having access to an already oppressive system. Trans justice on the other hand is about centering the leadership of trans and gender nonconforming people of color and demanding that society as a whole shift its ideas about gender and sexuality.

- Passing more hate crime legislation and building separate trans prisons strengthens the prison industrial complex that is already torturing Black and Indigenous trans people at epidemic rates. Advocating for hate crime legislation will not improve the lives of Black, Brown, and Indigenous trans folks.

- Tokenizing “trans women of color” only puts them on a pedestal without regarding their full and total complexity. This tokenizing often requires transfeminine people to be fabulous, resilient, and beautiful to get basic access to safety and dignity, instead of challenging the conditions that make their lives so precarious. Resist this tokenization and challenge any notion that there are “good” or “bad” representations of the trans community. Trans lives matter and censorship for comfort does not!

- Challenge the gender binary! It upholds very white and Western notions of what gender can be. Gender self-determination is important in challenging other forms of supremacy, like white supremacy.

[1] TDoR as cited in Lamble, 2008

[2] Lamble, 2008, p. 25

[3] Lamble, 2008

[4] Lamble, 2008

[5] Trans Lives Matter, 2020

[6] Human Rights Campaign Foundation, 2018, p. 3

[7] Snorton, 2017, p. 195

[8] Snorton, 2017, p. 195

[9] Snorton, 2017

[10] Butler, 2020, p. 59

[11] Preston, 2020

[12] Lamble, 2008, p. 38

[13] Shraya, 2018, Love is not Love

[14] Lamble, 2008, p. 38

[15] Forward Together, 2020

[16] Trans Day of Resilience, 2020

[17] Trans Day of Resilience, 2020

Selected Bibliography:

Butler, L. (2020). The forces of non-violence: An ethico-political bind. Verso.

Forward Together. (2020). Art as power. https://forwardtogether.org/programs/art-as-power/

Human Rights Campaign Foundation. (2018). Dismantling a culture of violence: Understanding anti-transgender violence and ending the crisis.https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/2018AntiTransViolenceReportSHORTENED.pdf

Lamble, S. (2008). Retelling racialized violence, remaking white innocence: The politics of interlocking oppressions in transgender day of remembrance. Sexual Research & Social Policy, 5(1), 24-42. https://doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2008.5.1.24

Preston, A. M. (2020, September 9). The anatomy of transmisogynoir. Harper’s Bazaar. https://www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/a33614214/ashlee-marie-preston-transmisogynoir-essay/

Shraya, V. (2018). Love is not love [Song recorded by Too Attached]. On Angry.

Snorton, C. R. (2017). Black on both sides: A racial history of trans identity. University of Minnesota Press.

Trans Day of Resilience. (2020). Femifesto for trans liberation. https://tdor.co/tools/femifesto/

Trans Lives Matter. (2020). Remembering our dead. https://tdor.translivesmatter.info/reports?from=2019-10-01&to=2020-09-30&country=all&category=all&view=list&filter=

Recent Posts

Standing Up for Student Rights: A Call to Action Against Bill 18

Celebrating Exceptional Leadership: The 2024 GSA Gala Award Recipients

Supportive and Knowledgeable are among the top ten characteristics of graduate students’ ideal supervision